2. Motivation

In the previous section, we established the fundamental programming paradigm of HDLs, in which hardware components are modeled as state machines. We also saw that de-facto HDLs such as SystemVerilog provide the low-level constructs needed to describe these state machines, giving designers fine-grained control over hardware behavior. At the end of the section, we identified several questions that arise when interfacing with components written in these HDLs. These questions intuitively highlight the challenge of ensuring that modules exchange values with a shared understanding of timing and validity constraints.

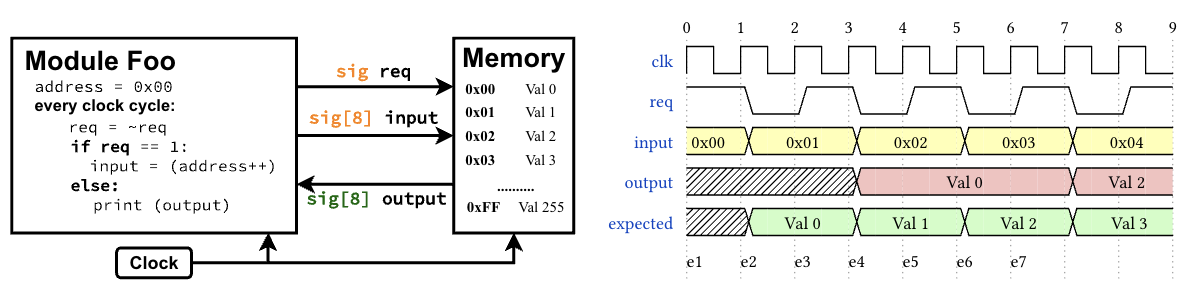

To illustrate this, consider the following example. The FOO module sends a read request (req) to a memory module and expects a response by reading the output signal. For clarity, the HDL code has been desugared into a software-style description. On the right, the waveform diagram shows the observed behavior of the system during simulation.

In this example, the FOO module sends a read request by setting the req signal high and providing an address on the input signal. The value of the input signal changes in the following cycle. The FOO module then expects the memory to respond with the data at the specified address by reading the output signal. However, as observed in the simulation waveform, the output data is not as expected. The value corresponding to the requested address becomes available only after two cycles. Furthermore, half of the address translations are skipped.

A closer inspection of the memory module’s implementation reveals the cause of this behavior. The memory module expects the input signal to remain stable for two cycles before it can produce the correct output in the next cycle. If the input changes earlier, the memory pauses its operation. As a result, when FOO changes the address and deasserts req after only one cycle, the memory stops processing the request and resumes only when req is asserted again in the next cycle. Consequently, the address 0x00 is translated after three cycles instead of one. Similarly, before the address 0x01 can be processed, the input has already changed to 0x02, causing the translation for 0x01 to be skipped entirely.

This kind of unintended behavior arises because intermediate values change during an ongoing computation. We refer to such problems as timing hazards. The root cause of the issue here is the lack of a shared timing contract between the FOO module and the memory module. The interface provides no information about how long input signals must remain stable or how long output signals remain valid.

In simple terms, timing violations occur when:

A component reads a value before it is ready or after it has become invalid.

A register storing state is overwritten while it is still in use.

Since components exchange values that are sourced from their internal state, such timing violations can lead to incorrect computations, data corruption, and unpredictable system behavior.

These issues motivate the need for:

Better abstractions for modeling hardware components and their interfaces.

A mechanism to specify and enforce timing contracts between components.

Anvil addresses these challenges by introducing higher-level message-passing abstractions, while still giving designers control over resources such as clock-cycle latency and registers. It allows designers to specify timing contracts directly in component interfaces. To enforce these contracts, Anvil’s type system reasons about the lifetimes of all values at compile time. It ensures that values are not used outside their valid lifetimes and that registers are not overwritten while they are still in use.

Hello World! in Anvil

Now it is time to write our first Anvil program!

In this program, we define a hardware process named Top using the proc keyword.

The process body begins with the declaration of a register counter of type logic[8], which represents an 8-bit-wide register.

Following this declaration, the behavior of the process is defined inside a loop construct. This models the fact that hardware processes run indefinitely and are naturally expressed as looping state machines. The loop body describes the behavior of the process in each iteration. In this example, each iteration performs two actions.

The first expression is a let binding that creates an intermediate value cnt. This value holds the result of incrementing the counter register by 1. The * operator is used to dereference the value stored in the register. Following this, we have a debug print statement dprint that outputs the value of the counter.

The >> operator is the wait operator. It indicates that the evaluation of the following term proceeds only after the previous term has completed. This operator helps model sequential behavior in hardware processes. The ; join operator is used to execute multiple expressions in parallel. For instance, ( t_1 ; t_2 ) indicates that both ( t_1 ) and ( t_2 ) execute concurrently, and the combined expression completes when both have finished. This is similar to a fork-join construct in software programming languages.

In this program, the let and dprint expressions execute concurrently. The loop waits for both to complete before proceeding to the next expression. In this example, both expressions are immediate, meaning they complete without consuming any clock cycles. The final expression is the set expression, which updates the value of the counter register by incrementing it by 1. This update takes one clock cycle to complete. Therefore, the loop iterates once every cycle.

You may have noticed that registers in Anvil are conceptually similar to registers in SystemVerilog. The let binding, which creates an intermediate value, is akin to creating a wire in SystemVerilog. Such a value is sourced from some underlying signal or register, and if that source changes in the next cycle, the wire’s value would normally change as well. However, Anvil’s type system prevents this from happening. Once a value like cnt is created, it is guaranteed to remain constant for the entire duration of its scope. This guarantee is enforced statically by the type system.

To illustrate this, consider the following modified version of the program:

Executing this code results in a compile-time error. The reason is that the value cnt is used on line 6, but the register counter is updated earlier on line 4. This violates timing safety, because cnt depends on counter. Anvil’s type system detects this error statically and rejects the program.

As a result, all values created using let bindings in Anvil are guaranteed to remain constant from the moment they are created until the end of their scope. This provides strong timing safety guarantees at compile time.