1. Background: The HDL Primer

The hardware description workflow starts with writing the hardware description in an abstraction called RTL (Register Transfer Level). For example, if you want to describe a simple adder in the most widely used HDL, SystemVerilog, you would write:

module adder(

input logic[7:0] a,

input logic[7:0] b,

output logic[7:0] sum

);

assign sum = a + b;

endmodule

This is known as the behavioral description of the adder. There is also a structural description, where logic gates are used as the most atomic primitives to describe the hardware. However, that is beyond the scope of this discussion.

At first glance, this SystemVerilog code might look like a regular software program. It appears as though we are assigning a value to an output reference in a function. But that is not the case.

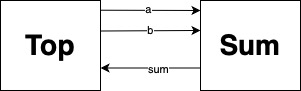

In software, you invoke a function using a call primitive, transferring control flow to it. In hardware description, however, module instantiation does not mean transferring control. Instead, it follows a communication paradigm – modules interact through signals (wires).

The signals are always connected and can be read anytime. The assign statement in the example above represents continuous assignment – meaning the value of sum is always the sum of a and b. There is no delay; the computation happens immediately. This is what is known as combinational logic in hardware. So whenever a or b changes, sum updates instantaneously. Essentially, the module behaves like a circuit that continuously computes the sum of its inputs.

Modelling Hardware Behaviours

Combinational logic models computations that are pure functions of the inputs. However, hardware behavior is often described using finite state machines. For this purpose, de-facto HDLs provide the abstraction of registers to model state-storing elements such as flip-flops and latches.

The state of a system is updated by a state function. This function is written over the current input values and the existing state values. The output of the state function is the next state, which is assigned to a register on the next clock cycle.

For instance, consider the following SystemVerilog implementation of a counter:

module counter(

input wire clk,

input wire rst,

output wire [7:0] cycle_count

)

logic [7:0] cnt_n, cnt_q;

assign cycle_count = cnt_q;

assign cnt_n = cnt_q + 8'd1

always_ff @(posedge clk or negedge rst) begin

if(!rst) cnt_q <= 8'd0;

else cnt_q <= cnt_n;

end

endmodule

This code describes a component named counter. The component takes a clock signal clk and a reset signal rst as inputs. It produces an output signal cycle_count, which represents the current counter value.

The body of the module first declares two local variables, cnt_n and cnt_q. Both are declared using logic. In practice, a SystemVerilog compiler or simulator infers whether a signal behaves as a wire or a register based on how it is used. By convention, s_n denotes the next state, while s_q stores the current state of the state variable s of the component. In this example, the state variable cnt simply stores the counter value.

After the declarations, two continuous assignments are defined:

assign cycle_count = cnt_q; and assign cnt_n = cnt_q + 8'd1.

The first assignment connects the output port cycle_count to the internal state register cnt_q. The second assignment defines the logic that computes the next state. This state function specifies that the next value of cnt_q is its current value incremented by 1.

The next state cnt_n is assigned to the state register cnt_q inside the always_ff block. The sensitivity list @(posedge clk or negedge rst) specifies that the assignment occurs either on the positive edge of the clock clk or on the negative edge of the reset signal rst. Intuitively, this means that the register is updated either during reset or on each clock cycle. Recall that the output signal cycle_count is mapped to the register cnt_q. Therefore, from the interacting module’s perspective, the component produces a new counter value on every cycle.

In summary, HDLs define a programming paradigm that is different from traditional software abstractions. In this paradigm, the designer describes a state machine. The states are stored in registers. The wires carry intermediate values that are derived from registers or are constant. The interfaces are also modeled using wires. These wires carry values at all times and are generally functions of the internal state.

Example : A Multiplier

Hardware designs often have a higher level state machine that defines the overall behavior of the component. Consider the following example of an 8-bit shift-and-add multiplier implemented in SystemVerilog:

TLDR : The shift and add algorithm is a simple multiplication algorithm that adds the multiplicand to itself based on the bits of the multiplier, shifting the result appropriately. For more details, refer to this link

module multiplier(

input wire clk,

input wire rst,

input wire [7:0] multiplicand,

input wire [7:0] multiplier,

output reg [15:0] product

);

// State definitions

localparam IDLE = 2'b00;

localparam CALC = 2'b01;

localparam DONE = 2'b10;

// Internal registers

reg [1:0] state_n, state_q; // State register

reg [7:0] H_n, H_q; // Upper part of product register

reg [7:0] L_n, L_q; // Lower part of product register (contains multiplier)

reg [7:0] M_n, M_q; // Multiplicand storage

reg [2:0] count_n, count_q; // Counter (3 bits to count up to 8)

assign product = {H_q, L_q};

always_comb begin

case(state_q)

IDLE: begin

H_n = 8'd0;

L_n = multiplier;

M_n = multiplicand;

count_n = 3'd0;

state_n = CALC;

end

CALC: begin

// Check LSB of multiplier (L_q[0])

if (L_q[0])

H_n = H_q + M_q; // Add multiplicand if the current bit is 1

else

H_n = H_q;

// Shift right {H_q, L_q}

{H_n, L_n} = {1'b0, H_q, L_q[7:1]};

// Increment counter

count_n = count_q + 3'd1;

// Stop after 8 cycles

if (count_q == 3'd7)

state_n = DONE;

else

state_n = CALC;

end

DONE: begin

state_n = IDLE;

end

end

always_ff @(posedge clk or negedge rst) begin

if (!rst) begin

state_q <= IDLE;

H_q <= 0;

L_q <= 0;

M_q <= 0;

count_q <= 0;

end

else begin

//Register updates

state_q <= state_n;

H_q <= H_n;

L_q <= L_n;

M_q <= M_n;

count_q <= count_n;

end

end

endmodule

The output signal product is sourced from the registers H and L. That is, product updates immediately whenever H or L changes, which happens every cycle. The register H stores the upper half of the product, while L stores the lower half. The register M stores the multiplicand, and the register count keeps track of the steps of the algorithm. Since this is an 8-bit multiplier, the algorithm takes 8 cycles to complete. The register state stores the current state of the high-level state machine.

The case block inside the always_comb block (which defines combinational logic) describes the high-level control state machine. It has three states: IDLE, which initializes values; CALC, which performs the shift-and-add algorithm over the state; and DONE, which indicates that the multiplication is complete and the product is ready to be read.

Although understanding the implementation of this multiplier is already somewhat tricky, the lack of human descriptions, comments, or clear naming conventions creates additional challenges for any interfacing module. Several important questions arise for a module that wants to use this multiplier. For instance:

How does the Top module know when the product is ready?

How does the multiplier module know when to start computing? Does it expect new inputs every 8 cycles?

Without reading the implementation, can an interfacing module answer these questions by looking only at the interface definition?

Do compilers or synthesis tools help prevent incorrect usage of the module?

These questions highlight the need for better abstractions in HDLs for describing hardware components. That is where Anvil comes in.

Note : The interfacing module is often called the Top module and will be referred to as such in the rest of this documentation.